Alexandra Moroti is part of the global customer research team at Amazon. Alexandra recently completed Birkbeck-UCL-IoE’s Masters in Educational Neuroscience degree. She was attracted to the course due to the novelty of the field, with its multifaceted approach of connecting different disciplines such as biology, neuroscience, and psychology with education – as well as the fact that it is a conjoined programme offered by three leading institutions. In this blog, we asked Alexandra to tell us about the independent research project she completed as part of her masters degree, in which she investigated educational games. Over to you, Alexandra.

“A quick search for “educational toy” on Google yields 191 million results in under a second, most of which are blog posts with affiliate links or recommendations from media outlets. A search for “educational toys” on Mumsnet, a popular parenting blog in the UK, shows numerous inquiries seeking age-appropriate recommendations. While many articles highlight the best educational toys for specific age groups, there are often no clear criteria for selecting these toys.

The purpose of educational toys is to aid a child’s development in a specific area, such as teaching coding or promoting motor skills. These toys should be active, engaging, meaningful, and socially interactive. However, the labelling of toys as “educational” is not regulated, and the development of educational toys often lacks sufficient research into age-appropriate developmental principles relevant to the claimed outcome.

To evaluate the claims of a popular toy marketed as enhancing social cognition in children through socio-emotional learning, I conducted a small-scale pre-test/post-test experimental design, to investigate the effects on young children of playing with a particular “educational” toy over a period of 14 days.

The selected toy

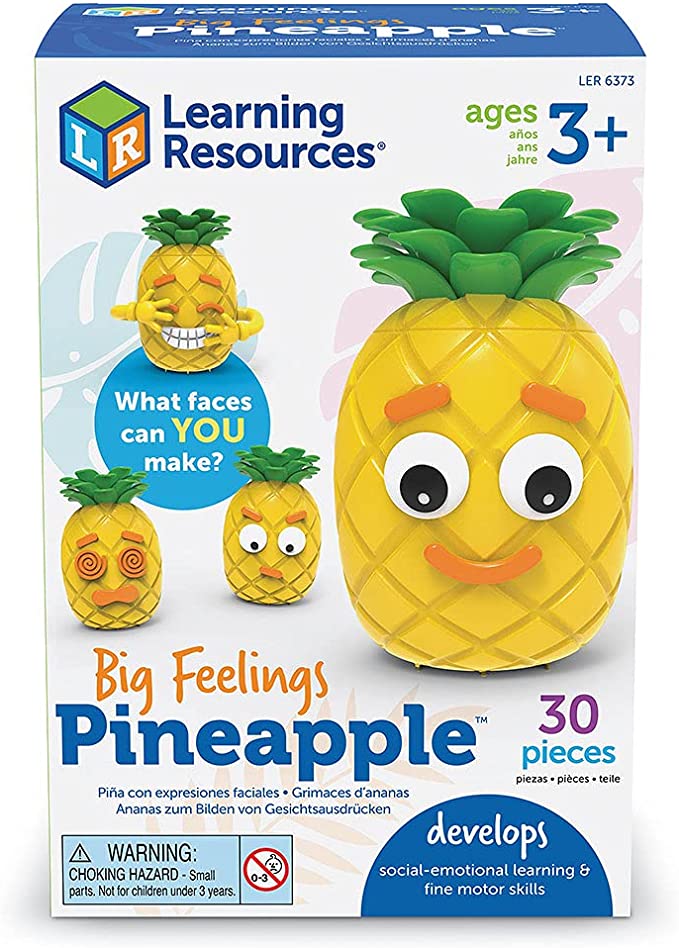

The toy selected for the research was ‘Big Feelings Pineapple,’ marketed for children aged three years and above. The aim of the toy is to build preschool social-emotional learning skills by supporting the recognition of emotional facial expressions. The toy came with a leaflet of 24 expressions, including the six universal emotions: happiness, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, surprise, which can be constructed using various pieces including eyebrows, eyes, and mouths. Here’s the product image (taken from its Amazon page).

The study

The study

Child participants played with the Pineapple toy and were assessed before and after the intervention on four tasks – two experimental and two control tasks. I evaluated the child’s interaction with the toy through an in-the-moment play assessment tool, and then coded parental observations from a daily play diary.

I found that, although the Pineapple toy was good at promoting communication, it scored lower than predicted in the “Thinking and learning” and “Social interaction” dimensions of my measures. Children were mostly engaged with the toy when their parents were involved, but the toy lacked context and explanation when used alone. Parents who engaged their children with the toy in a meaningful way had more in-depth conversations about emotions later in the trial, and the toy was seen as a positive facilitator for conversations on emotions.

The children showed higher levels of emotion recognition post-play than they did pre-play, but the improvement was not related to the number of times the child played with the toy. This makes it ambiguous whether it was the toy having the effect or natural development. I wish I had included a ‘control group’ of children who had played with another type of toy, to check for this!

Broader lessons from my research study

While initiatives like Common Sense Media exist to help parents choose the best products for their kids, they do not include educational toys. Recently, some researchers have started to pay closer attention to the overuse of the label “educational” in marketing toys, with some researchers also turning their attention to educational value of “educational” apps. For example, see papers by Kathy Hirsh-Pasek and colleagues, Marisa Meyer and colleagues, and Shayl Griffith and colleagues.

In my view, an important future step is to establish guidelines for the development, marketing, and testing of educational toys to ensure that they are truly beneficial for a child’s development. This could involve consultation with researchers in the field, qualitative research such as focus groups and in-depth interviews with stakeholders, and longitudinal studies to assess the educational claims made by manufacturers. By doing so, parents can make informed decisions about which toys truly aid their child’s development. But my study suggests that a key role for toys may be how they support interactions between parents and children that in turn stimulate learning.

I think children’s learning should be a collective effort that goes beyond the household. Society should ensure that cities and environments, curricula, and manufacturers’ claims support educational experiences that prepare children for a future where adaptability and mental balance are crucial.”

Thanks, so much, Alexandra! If you are interested in this topic, take a look at this article which considers whether toys and games improve children’s thinking generally or just make kids better at playing games. And this article by Yuval Noah Harari, the author of Sapiens, speculating on what skills children may have to learn in 2050!