Do you believe in love at first sight?

Do you think that opposite attract?

Can Paracetamol help you cure your heartbreak?

Sitting at a dimly lit table full of glittery hearts and candies, I consider Gilly Forrester’s questions to the audience. Yes, No, No, I reply. Having a look at the rest of the audience – maybe in the hope of finding my soulmate, I can see that some people do not agree with me. The tone is set: what I will hear tonight will challenge my preconceptions.

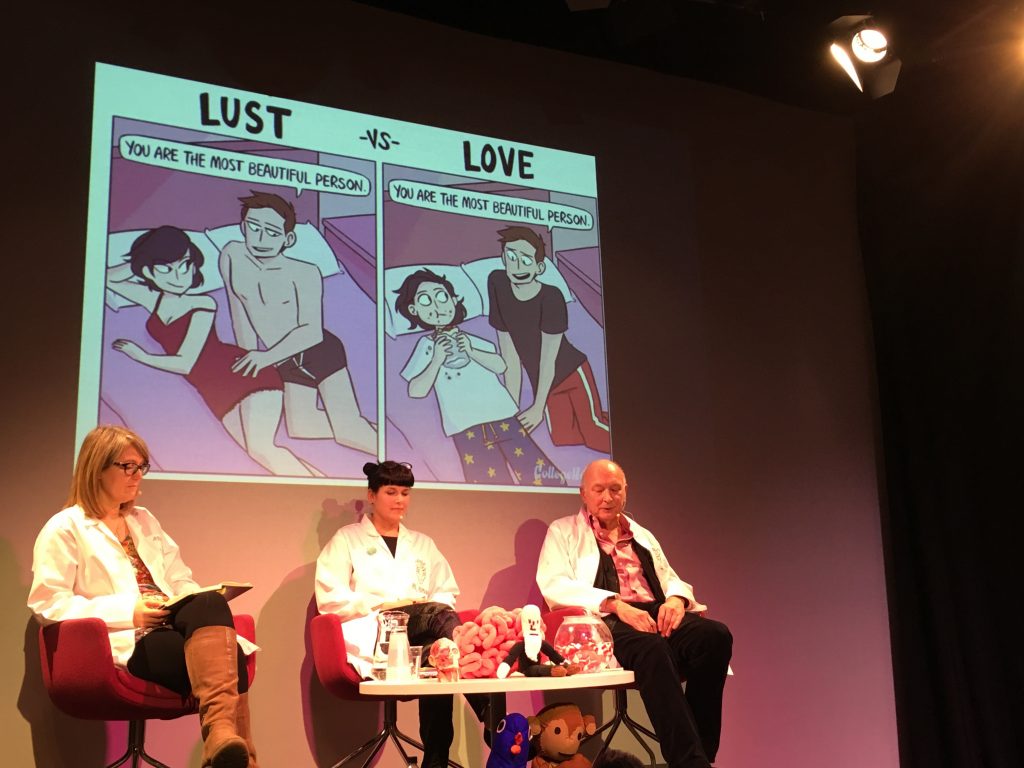

Joining Gilly on stage, we have Catherine Loveday (no, she did not change her name for the event, it is just very appropriate), and Simon Green. Catherine is a Professor at the University of Westminster, and is here to reveal the physical chemistry of lust and love. Simon is a retired Senior Lecturer at Birkbeck University, and will tell us about the evolutionary functions of lust and love, in humans and other animals. Gilly Forrester, who created this overall event, is a Reader at Birkbeck University, and will talk about other species, such as birds and white wales – thereby also considerably raising the “cuteness” vibes of this event.

But let’s start with us, humans, and let’s clarify what we mean by Lust and Love.

Catherine explains 3 different states:

- Lust, or physical, sexual attraction. One of the 7 deadly sins. Bluntly speaking, this is what is behind hook-ups and one-stand partners – multiple people can satisfy our needs here.

- Romantic love, or passion. Here, the attraction is still physical but we select one person to be in a relationship with. Our brain is secreting addictive dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin. Have you ever felt so much passion that you could not eat anymore? Well, this is because heightened rates of noradrenaline are also related to loss of appetite.

- Attachment, or companionate love, is a calm, secure long-term relationship with a “partner for life”. Here, our brain secretes oxytocin, the “cuddle” hormone. It is also related to maternal love.

These three states are not mutually exclusive, but since attachment develops over time, we might reconsider our first question “Does love at first sight exist?”. Well, maybe we should instead say: “Lust at first sight”?

Catherine, on the left, explains the three states of lust and love

And what about gender differences here? Simon mentions that the costs and benefits of lust and love might be evolutionarily different for men and women. Whereas men would benefit from having many different sexual relationships (spreading their genes), women are more constrained by the costs of pregnancy, needing to carefully select the good partner (i.e. good genes), while also providing resources and security to the future offspring. Following from that, as men have no guarantee that an offspring is theirs (they are not pregnant), they would be particularly sensitive to sexual infidelity, whereas women would need to rely on attachment and security, thereby being sensitive to “attachment” infidelity. Should I just say here that we are talking about evolutionary psychology, so if you feel some outrage here (for god’s sake, we are in the 21st century!), just imagine a world with more pregnancy risks (without condoms and contraceptive pills) – the evolution of species is much slower than that of technology, and we talk about the reproduction of genes here.

What kind of signs do we use to select a good partner then? To try and figure it out by ourselves, we answered a little survey, selecting our physical preferences among different options. I happily did it – the answers were anonymous, right(?!). Few indicators came out when merging the answers from the audience, that correspond to what is usually found in the general population. For example, women are considered more attractive if they have long legs, compared to their upper body (hence maybe the power of heels), and if they have a narrow waist and larger hips. When it comes to judging men, on the contrary, a more balanced legs-to-body ratio is preferred (legs a bit longer than the torso but not too much). For both sexes, indicators of good health are usually preferred. This includes symmetry, and having a rather thin face. Of course, in social interactions, as well as on dating apps, physical indicators come along with information about a person’s social status and personality. This also influences attractiveness. Creativity also enhances a man’s attractiveness from a woman’s perspective – much more than the other way around. So sadly, if I create a profile on a dating app, mentioning that I am playing music might help less than putting a picture of me in a fancy dress…

A funny fact though, is that whereas women’s choice of attractive mate age increases with their own age (red line on the picture below), men’s preference for mate choice never exceeds about 20 years of age – regardless of how old they are (blue line).

Let’s try and justify this: if we consider that older women have had, on average, more sexual partners, dating younger women with less experience would help men to be sure that the offspring is theirs. On the woman’s side, a man who can provide resources would gain attractiveness as he can provide security for the offspring. Again, we are talking about evolutionary psychology here, and customs have changed in western industrialised countries. A key challenge of these theories is to make sense of different patterns of relationships (e.g. homosexual, pansexual relationships) and social configurations (e.g. taking into account the availability of contraception methods, and the increased independence of women in society). Maybe these evolutionary theories, focused on very long time frames, could be complemented with social and cultural theories. However, they can help us to understand what were share with other animals.

Inasmuch as we fancy talking to our cats and dogs, it is hard to know what is going on in their heads: Do they feel lust, love, companionship? Back in the 19th century, a strong movement in Psychology, called Behaviourism, focused on what was observable for an external eye, that is to say, behaviour, acts. Taken to an extreme, it would mean that we could infer love in animals to the extent that they show similar behaviours to ours. But it is not only about animals being similar to us. We are also similar to animals, since our brain is the repository of evolution.

The 3-brains theory posits the existence of 3 layers in the brain (for further clarifications, see this page):

- The reptilian brain, shared with various, and quite remote species such as amphibians, or reptiles. It controls our vital functions (such as breathing, body balance) and primal emotions (seeking for food and partners, lust, rage).

- The limbic brain is shared with some reptiles and mammals. It involves the regulation of emotions that are more related to attachment: the urge to care for an offspring, to have long-lasting relationships. It can record memories of behaviours that produced agreeable and disagreeable experiences.

- The cortex, often highlighted as the most developed human part, is actually present in other species as well. What seemed to have particularly expanded in primates and humans is its connections with other areas of the brain. The cortex helps us to regulate our behaviour and refrain impulses, but it would not work without foundations, in other words, without the reptilian and limbic brains!

So, in answer to the question: “Do we experience the world in a similar way than other animals?”, a tentative response would be: could be, for lust and romantic love.

This is supported by the study of brain chemistry. Oxytocin is not only secreted by human brains. In animals, this hormone is related to pair bonding, which basically means pairing to handle resources and raise offspring. Pairing fosters health and survival. The good news is that the secretion of oxytocin, in both humans and animals, enhances the attractiveness of our current mate, and reduces the attractiveness of other mates. Another good news is that the physical symptoms of a heartbreak can be alleviated via paracetamol – of course, this is not the panacea to cure any psychological and mental health issue.

This is supported by the study of brain chemistry. Oxytocin is not only secreted by human brains. In animals, this hormone is related to pair bonding, which basically means pairing to handle resources and raise offspring. Pairing fosters health and survival. The good news is that the secretion of oxytocin, in both humans and animals, enhances the attractiveness of our current mate, and reduces the attractiveness of other mates. Another good news is that the physical symptoms of a heartbreak can be alleviated via paracetamol – of course, this is not the panacea to cure any psychological and mental health issue.

At this stage, my brain was a bit smashed by all these new ideas – and by my two glasses of wine. So, what did I take from the event? First, next time I am heartbroken, I will go to the chemist, pull out a 50p coin and buy some Paracetamol. Second, I might stop making fun of my mum when she infers mental states in cats.

The next Psyched! event is about Sex differences. You can book your place here.

Don’t forget to follow the team at @Me__Human

Written by: Jessica Massonnié