As part of our series of blog posts written with/for educators and school leaders, we had the pleasure to interview Nathan Morland. Nathan is the Director of the Staffordshire Research School. As such, he infuses his work with educational research, while being aware of and attentive to his staff’s needs and aspirations. In this interview, he shares his experience and key resources with us.

What does educational neuroscience mean to you?

For me, it means expanding foundation in our level of understanding about cognitive development and how young people acquire and enhance knowledge and skills, and more importantly…remember them! It also means a number of opportunities and challenges for teachers and school leaders too.

I cast my mind back to when I started out in teaching 15 years ago and I don’t recall the word ‘neuroscience’ featuring in CPD or department meetings. Enhancing or evolving practice seemed to be much more organic, based upon feedback from a middle or senior leader, with little evidence or research from neuroscience used to back it up.

On occasions the term ‘research-informed’ can be carelessly misused or superficially applied to strategies without the true depth of research findings being fully explored or understood. There are many green shoots though with growing traction and a sense of enthusiasm in research-informed practice in the profession. Pleasingly, the drivers of this movement are from both bottom up (Research Schools Network, twitter, new authors, researchED events) and top down perspectives (School Inspection Framework overview of research).

The Challenges are very apparent too. The NFER’s recent report on teachers’ engagement with research indicated that only 16% of the teachers surveyed said decisions about their CPD were based on academic research and, ‘teachers were most likely to draw on their own expertise, or that of their colleagues, when making decisions about teaching and learning or whole-school change’. (NFER, 2019)

So there is still a great deal of work to do. How do we distil complex and specialist research into a digestible format, that enables our time-strapped teachers to apply them effectively in their bespoke contexts? The EEF’s Guidance Reports do a great job of the distillation process, alongside the Research School Network in mobilising the research and providing the practical tools for their application.

What does that mean for you to be involved in a Research School?

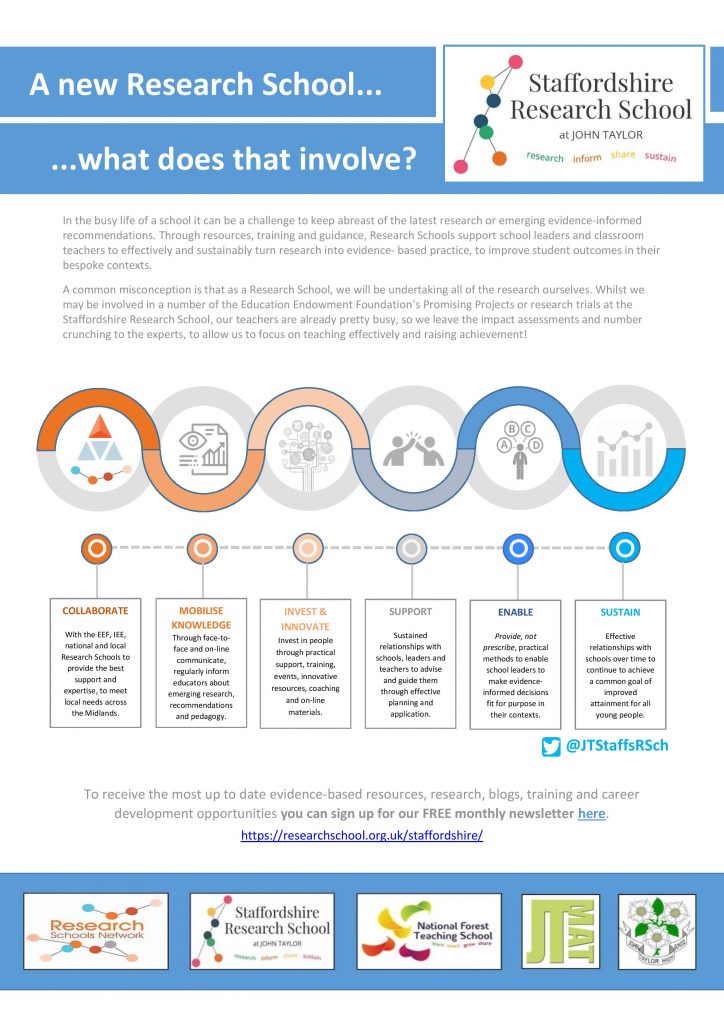

The most common question we were initially asked upon becoming Research School was ‘What does that involve?’ One of our first steps was to paint a clear picture of what Research Schools do, and do not do. This can be seen in our concise infographic and blog here. This question is then increasingly being followed up by, ‘so how can we work together?’

It is a privilege and provides an additional sense of purpose. It means there is an additional (and non-judgemental) avenue of support for schools to enhance outcomes for their students, particularly in areas of deprivation, that are free from Multi Academy Trust, Local Authority, Teaching School or geographical alliances and loyalties.

How do you keep up to date with new neuroscience research?

It is a challenge with the amount of emerging research.

- As the Director of the Staffordshire Research School, being part of the Research Schools Network enables us to learn directly from the colleagues at the EEF and the IEE. It also means we are directly engaged in working with schools to apply research in a range of settings, which will only be effective if we have a broad foundation of knowledge ourselves.

- I receive a range of newsletters and journals including ResearchED, The Chartered College Impact Journal, ASCD (in the USA) and Best Evidence in Brief from the IEE.

- In the John Taylor Multi-Academy Trust and via the National Forest Teaching School we invite the researchers to share expertise at our training and conferences. The value of face-to-face interaction and training with researchers can be underestimated, as some schools can be cautious about releasing staff for training to save cover costs the risk can be a lack of depth of understanding and possible weaker implementation models.

- Twitter is great. I rate it as one of the best sources of information and collaboration I have and would encourage any non-users to take the plunge.

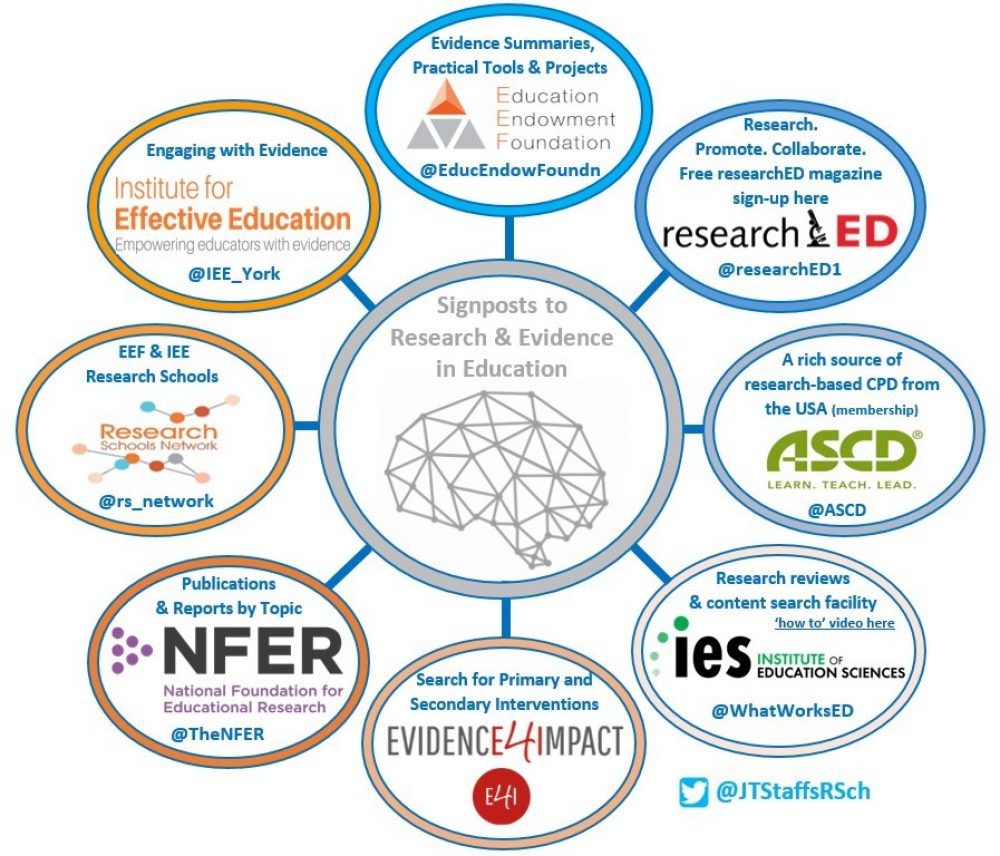

- I also have a set of go to organisations that I check in with regularly for updates. You can find these in a free handout and hyperlinked infographic here.

From a practical point of view, I take a fairly methodical approach using two IT tools called Pocket and Padlet. Whilst these are not evidence based, they are simply practical tools that help me filter and organise the sources of research and reports that I come across and leave a breadcrumb trail back to where I found them. I put sources of research, reports or blogs in the Pocket app (a simple tap and drop feature), either to read or come back to at a later date. When ready, I then upload the link to a Padlet page. Padlet is virtual pinboard that enables people to bring together and store a range of e-resources in one place. I can then categorise it for colleagues, delegates or for personal use into aspects of research, evidence, pedagogy or school focus area and save time in having to search the internet all over again. Its power is in its simplicity and you can see an example here.

How do you get teachers and students involved?

- Each Monday we hold short briefing that is supported by a takeaway resource (maximum of one page of A4 or a postcard) that covers a ‘nugget’ of research-informed practice and links with one of the T&L principles in our ‘inside-out’ CPD model (see question below). It keeps the flow of research regular and digestible for staff.

- Staff receive a ‘DNA’ paper each half term. A deeper insight into an element of research, again linking to one of our key T&L principles (e.g. Long Term Memory) or school targets (e.g. Pupil Premium students). This introduces the research concisely and provides a number of signposts to journals, white papers, podcasts or guidance reports.

- Practical teaching methods and templates are created and provided to staff each half term to model how to turn the research into a tangible teaching methods or resources and how to articulate them to students.

- In addition to the training courses, free twilights and more sustained work with schools across the West Midlands, colleagues also receive the Staffordshire Research School’s newsletter which is free to sign up to here.

In all honesty, the students get involved through their lessons. We keep it simple, they already have a lot on their plates. We do not necessarily teach them explicitly about neuroscience research but we do model practices for learning and help them to experience what successful learning feels like through well-designed lessons and tasks.

Can you give some examples of how neuroscience understanding has helped you as a school leader?

It has allowed me… no us, as a leadership team… to:

- Provide precise informed feedback where practices have been less effective e.g. a retrieval practice starter done with books open or resources is not retrieval practice, in turn allowing staff to adjust and improve.

- Upskill staff in their pedagogical knowledge through the design of a CPD model that is built upon a solid foundation of emerging research.

- Consider the extent to which staff are engaging with research and provide a range of timely tools that allow staff to do so at different depths (briefings, 15 minute reads, full reports, extended CPD)

- Provide focussed training opportunities at John Taylor High School, the National Forest Teaching School and the Staffordshire Research School.

It has helped significantly, however the amount I learn from our most innovative and well-read staff means that they help me equally in return.

Can you give some examples of how a scientific approach to education has helped your school?

At John Taylor High School we operate an ‘inside-out’ CPD model whereby, informed by previous student outcomes and middle leader guidance, staff select an area of T&L to improve from a range of T&L principles (the Rosenshine Principles feature heavily). It is a ‘bottom up’ model that is very personalised and takes inspiration from Huntington Research School’s ‘Disciplined Inquiry’ and Durrington Research School’s six principles of evidence-informed teaching. This year alone, 48 staff have chosen Long-Term Memory & Retrieval Practice foci and 30 more have chosen modelling, scaffolding or the teaching of disciplinary literacy. Each member of staff has a Coach to engage in reflective practice, alongside the use of Iris. A key component of our ‘inside-out’ model is that staff are expected to engage with reading research (supported by the Padlet example here) and implement the strategies in their classrooms, with key milestones calendared over the course of the academic year. Autonomy remains with the teacher and they are encouraged to trial and test methods – but the curriculum design, craft of lessons and decision making have to a rationale in that they are informed by research.

Are there areas where you think research should focus next (ie what are the important gaps in our understanding)?

The evidence behind dual coding and cognitive load theory is sound. However, some teachers’ interpretation of how they combine this research to design/present their teaching resources can be varied and cause the two to be in conflict with each other. The desire to include dual coding can unintentionally cause some teachers to create cognitive overload for students. Finding the balance and optimal combination of each is less understood. I’d like to see more exploration of how the design and presentation of teaching resources that integrate different ratios of both cognitive load theory and dual coding. Having the same teacher, teaching the same content, using resources designed with these in mind would be interesting.

That said, the variables of the students themselves and over 240,000 bespoke school contexts across the country will always remain, rendering any research a ‘best bet’, not a ‘sure bet’ of what could work with the correct implementation.

Thank you very much for your time!

You can follow the work of Nathan’s research school @JTStaffsRSch