We were delighted to welcome Rae Snape, headteacher at The Spinney Primary School in Cambridge, and Dr Sara Baker, University of Cambridge, to the CEN yesterday. They shared their experience of working together, and what they’ve learnt from that process about developing projects together as researchers and educators. Here is a short summary of their talk:

Creativity in primary school children

Yesterday’s CEN seminar considered creative cognition in primary school age children and particularly the double-edged sword of cognitive control. You can see a 1 minute video summary of Cathy Rogers’ talk here.

What if… we were able to say more about how the brain learns?

By Su Morris, PhD student

Debate at UCL IoE on 15th May 2018

Panellists:

Becky Allen, Director of the Centre for Education Improvement Science, UCL Institute of Education (IOE)

Steven Rose,Emeritus Professor of Neuroscience, the Open University

Cat Sebastian,Reader in the Department of Psychology, Royal Holloway, University of London

Michael Thomas, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at Birkbeck, University of London, and director of the Centre for Educational Neuroscience (CEN)

Discussion chaired by:

Becky Francis, Director, UCL Institute of Education

This fascinating debate set out to explore what can be expected from educational neuroscience for policy and practice, as well as how to recognise ‘neuro snake oil’ (see here for the CEN series on neurohits and neuromyths). Each panellist introduced their viewpoint and initial thoughts:

Michael Thomas began by saying that we learn because the brain is plastic, i.e. pathways and connections in the brain are made and changed based on our experiences. The problem is that learning is a complicated process with seven systems interacting in the brain, all varying in their development and in their sensitivity to socio-emotional factors. Understanding learning is also challenging as it is only one aspect of a very complex educational system. There are two main ways that neuroscience can be translated into something useful for teachers – understanding brain health so students are ready to learn, and understanding how learning takes place in different subject areas. He concluded by saying that although it is a challenge, it is one worth pursuing.

Becky Allen highlighted the impact of having an incomplete understanding of cognition, particularly the lack of confidence in cognitive theories, which are important for generalising across different groups of children and classrooms. Currently, ideas such as pretesting, redundancy, and desirable difficulties are being promoted by some influential figures in education, however these run the risk of being the new myths – they are based on a small number of studies with short-term outcomes. The key question is whether ‘learning how we learn’ will help us know how to teach. Each class group has around 30 individual learners, meaning that teachers spend the majority of their time with the group rather than considering learning at an individual level.

Cat Sebastian outlined the positive influence of neuroscience on understanding the adolescent age group; why teens behave like they do, and how connectivity in decision-making and emotional regulation continues to mature in this age group. This can help both teachers and students understand changes in risk-taking behaviours and the changing influence of peers. Neuroscience can also help explain why different interventions may be more successful with some groups than others, and can even motivate wider research in particular areas; e.g. there had been very little research on adolescence until neuroscience showed that development continues into and beyond this age group.

Steven Rose began by making the point that it is children who learn, not brains. Brains are embedded in children who are embedded within a school and society. He questioned whether answering questions about the brain can really help with learning and teaching. It may even distract from things that we do know and need to respond to, e.g. food banks in order to meet the current needs of students. Many of the neuromyths, including VAK (visual, auditory, kinaesthetic learning, or learning styles) and brain gym were considered ‘good science’ a couple of decades ago. He closed by predicting that some of the current developments in techniques and technologies may well turn out to be neuromyths of the future.

Becky Francis summed up the opening comments as three important considerations: 1) risks of early adoption of scientific ideas and fads; 2) the importance of interaction between different disciplines, and 3) considering the wider educational context.

The Q&A session drew out further themes and practical applications, but an important first question was about different timescales. Translation into practice needs to be evidence-based, and it is important to have intervening stages between neuroscience and practice – perhaps this is a new profession in itself? An analogy was drawn with medicine, which has taken 200 years to get to a position of being research-led but where doctors still treat the person. Scientists may take years to develop understanding; policy-makers have about 18 months; teachers need something for Monday morning! A way of managing this is to balance the time and disruption of changing practice, against the risk factors. For example, spaced learning has a one-off disruption and time cost, but it is not likely to be damaging, and therefore on balance may be something teachers could introduce.

The panel then responded to questions from the floor.

When asked about mental health, they highlighted the importance of shaping policy for allocating resources, but that neuroscience has a role in identifying risk factors, understanding of resilience, and how early life stresses can have long-reaching impacts on brain development.

A question on cognitive load theory (amount of information that can be held in working memory) highlighted the fact that some ideas may be introduced more easily because they are easily implemented, and help to make sense of the wide variation across a class. However, it may also lead to inappropriate expectations about how behaviour can be changed; e.g. training working memory does not lead to gains in other areas.

Finally, a question about funding research emphasised the importance of multidisciplinary research, where funding could be allocated on the basis of a problem to be solved, rather than being discipline-focused.

The session concluded with an opportunity for attendees to identify areas they would like neuroscience to answer, such as concerns parents may have about whether they have passed on difficulties or challenges to their children e.g. in maths.

This well-attended event emphasised once again the interest people have in understanding how knowledge about the brain may inform teaching practice and improve children’s learning. One important outcome from the discussion was the importance of multidisciplinary research; not only between education, psychology, cognitive science, and neuroscience, but also with social disciplines. The context of students’ learning is important and needs to be considered. Also, many are aware of neuromyths which has led to a certain amount of cautiousness about adopting new ideas before they are fully researched. Therefore, there is a balance to consider between time commitment and disruption vs risk. Overall, there was general agreement that it is useful and important to understand ‘why’ – why some interventions are more successful with some than others; why some children respond to certain teaching methods better than others; why there is such variation within and between each class. Through exploring answers to these questions, educational neuroscience will have something to offer to teachers and learners – but it is unlikely to be ready for Monday morning!

Click below to watch the video of the event:

CEN seminar: What’s involved in designing and evaluating an education intervention?

Thank you to Dr Sveta Mayer for a fascinating discussion about her journey towards designing and evaluating an education intervention. The intervention involves computer-based activities which encourage children with autism to work out what animated characters are feeling and why. They can then relate this understanding to comparable social interactions in the real world.

Here is a summary of her talk.

Design and evaluation of an education intervention for children with autism targeting social and emotional engagement through observation.

by Dr. Sveta Mayer, Lecturer. UCL Institute of Education

Sveta Mayer (PhD), lecturer at UCL Institute of Education, discussed her recent research project called See+ Autism at yesterday’s CEN research group session. The project involves the design and evaluation of a computer-based educational tool to support autistic children’s social and emotional engagement. This involves children observing animations of virtual characters engaged in social scenarios.

Sveta discussed how she met the challenge of evidence-based research, policy and practice related to educational neuroscience to inform her research by drawing upon a multidisciplinary review of literature to inform her work. She also discussed why a participatory research approach involving practitioners-as-researchers is invaluable to address the challenge of ecological validity, i.e. supporting transfer of children’s computer-based learning into their lived experience of the social world around them.

Sveta discussed how she met the challenge of evidence-based research, policy and practice related to educational neuroscience to inform her research by drawing upon a multidisciplinary review of literature to inform her work. She also discussed why a participatory research approach involving practitioners-as-researchers is invaluable to address the challenge of ecological validity, i.e. supporting transfer of children’s computer-based learning into their lived experience of the social world around them.

Sveta hopes to draw on her findings to establish a blended learning education tool incorporating computer-based learning augmented by practitioner-based support. Sveta carried out foundational work for this project as part of the UnLocke project (http://unlocke.org) and also received UCL seed funding.

Educational neuroscience… or (if you want a jazzier title)… Killer robots and how science works in the brain!

Blog written by Prof. Michael Thomas for the HMC (Headmasters’ and Headmistresses’ Conference) introducing educational neuroscience.

If you’re of a nervous disposition, it’s not a good time to read the news. Even the technology pages, once a place of respite, now tell us that artificial intelligence is a danger, at risk of taking over the world, or at the very least, stealing our jobs. Its powerful learning algorithms can sift through mountains of data to log our every move.

Are computers now better at learning than humans? How much do we now know about human learning itself, given our greater understanding of how the brain works? And are these insights of use to educators?

Educational neuroscience is a scientific field that seeks to address these questions, by bringing together researchers from neuroscience, computer science, psychology, and education to explore how new insights into brain mechanisms of learning can inform educational practice (see https://impact.chartered.college/article/brookman-byrne-neuroscience-psychology-education/).

Human learning is (trusting somewhat in evolution, here) well adapted to the natural environments we have found ourselves in, but it nevertheless appears somewhat idiosyncratic when applied to education. Consider these questions:

- Why am I liable to forget that the capital of Hungary is Budapest, but not forget that I’m afraid of spiders?

- Why do I find I have learned things better after a good night’s sleep?

- Why does my mind go blank when I’m stressed in an exam?

- When I became a teenager, why did I sometimes do stupid, occasionally dangerous things just to impress my friends?

- Why can I learn a new language so much more easily when I’m 5 years of age than when I’m 50?

If one were designing a machine to learn (of the sort intended to one day take over the world), one could imagine designing it without any of these properties. For example, the machine could store Capitals-of-European-Countries and Animals-I’m-Scared-Of as similar types of memories, and it need not forget either. One could build the machine without emotions like ‘stress’ or ‘anxiety’, which on the face of it seem to detract from human learning performance. And, battery life permitting, one could build a machine that didn’t need to sleep to achieve efficient learning. The reason why humans show these particular idiosyncrasies in learning lies in the particular way our brains work, because of its particular biological origins.

Educational neuroscience as a field is still in its early days. It is building a foundation of basic science of neural mechanisms of learning. One place to start is to understand the reasons why some of the best methods that teachers use are indeed so effective. Perhaps there will also be insights that offer new techniques to teachers.

The field is not without risks. The complexity of learning in the brain and the state of current scientific knowledge mean that there is a risk of premature translation before the foundation is established. The risk is heightened by the legitimate desire of policymakers to use scientific evidence to inform their education policies, the enthusiasm that educators have to inform their teaching with insights into how the brain works, and the desire of commercial companies to sell new techniques to schools using the latest neuroscience findings merely as window dressing (for some fun reading, see http://www.educationalneuroscience.org.uk/resources/neuromyth-or-neurofact/).

Nevertheless, projects are underway to evaluate new potential teaching techniques based on neuroscience insights (see http://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/news/new-research-to-investigate-if-neuroscience-can-improve-teaching-and-learni/). And the science of learning is far enough progressed to begin to draw a broad picture for teachers relevant to the classroom (e.g., https://impact.chartered.college/article/howard-jones-applying-science-learning-classroom/, https://www.amazon.co.uk/Neuroscience-Teachers-Applying-research-evidence/dp/1785831836).

I’ll give an example of the kind of work currently underway in my research centre, the Centre for Educational Neuroscience (http://www.educationalneuroscience.org.uk/). The UnLocke project (http://unlocke.org/) was inspired by the observation that learning in maths and science sometimes involves inhibiting prior beliefs or direct perceptual information. For a child to learn that the Earth is round requires inhibiting or suppressing his or her previous experience that it seems to be flat (at least when you play football on it). Experts in science and maths get better at inhibiting prior knowledge rather than overwriting prior concepts with new ones.

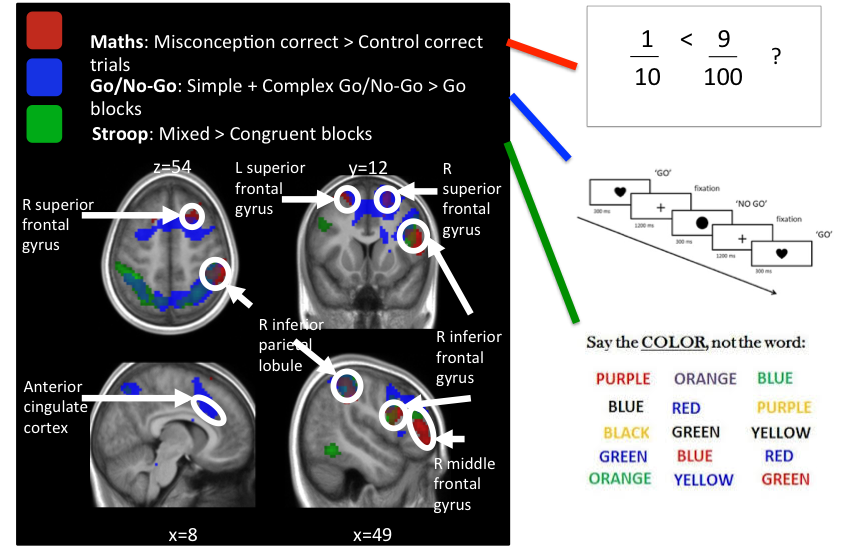

The fact that we can visualise the brain operating with modern scanning methods provides key insights here, because it’s hard to see people inhibiting knowledge in their overt behaviour. Inhibition is the brain stopping us doing things. We know the sorts of tasks that require inhibition. Say you’re shown a sequence of cards that either have a heart shape or a circle on them, and you’re asked to press a button onlywhen the heart appears. The sequences of cards flashes up, you’re ready to press the button, but if the circle appears, you have to stop yourself from pressing the button. Or say you’re shown a series of colour names (BLUE, RED, GREEN) printed in different coloured text, and you’re told to name the colour of the text, not name the colour word. It’s so easy to name the colour word, you want to say the colour word … but you have to stop yourself, and name the text colour instead. We can see regions at the front of the brain working harder in a functional magnetic resonance imaging scan when adolescents are asked to do these tasks (see below). Annie Brookman-Byrne, a PhD student at Birkbeck College, asked the same teenagers to solve counter-intuitive maths problems while in the scanner. They might be asked, is one tenth less than nine hundreds? The answer is YES, but part of you wants to respond NO, because the numbers in nine hundreds are bigger. When Annie analysed the results, she found the same inhibitory brain areas become active in solving the counter-intuitive maths problems as when stopping pressing buttons or reading colour names.

Taken from: Brookman, A., Tolmie, A., Mareschal, D., & Dumontheil, I. (2016). Science and maths reasoning and inhibitory control in adolescence: An fMRI study. Poster presented at IMBES conference; Toronto, Canada.

It’s one thing to gain insights into the brain mechanisms involved in learning maths and science, another to make suggestions about how this may translate to the classroom. Insights must be transformed by pedagogical principles into learning techniques that may be useful for teachers in the classroom, which in turn must be evaluated for their effectiveness by behavioural trials.

In this way, the UnLocke team have design a computer-based learning activity for use in science and maths classes to encourage 8 and 10-year-old children to ‘stop and think’ when they are reasoning about maths and science problems, and we are currently evaluating its effectiveness in 90 schools around the country (https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/projects-and-evaluation/projects/learning-counterintuitive-concepts).

A word of warning. Don’t believe in a teaching method just because there’s a brain image next to it! (see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2778755/).

Educational neuroscience is part of an evidence-based approach to education, which means you should believe nothing until you see evidence that a teaching technique really works. In this case: that improving kids’ inhibitory control skills when thinking about maths and sciences problems will improve their end of year performance on science and maths tests! Keep your eyes peeled for the results of our study.

Meantime, back to killer robots…

Montessori education: what’s the evidence?

Watch Prof Chloe Marshall’s one minute summary of her talk on Montessori education. To find out more about the existing evidence, you can read her review paper here.

Find out about baby brains

On Thursday 25th January, the CEN had a visit from Dr Silvia Dalvit, founder and director of the company Babybrains. Silvia, a cognitive neuroscientist and Birkbeck alumna, explained to us how she has created an app for new parents. The app gives parents weekly age-appropriate science-based activities, each only a few minutes long, to try out with their baby. These activities target different areas of babies’ language, perceptual, social and motor development.

Dr. Dalvit said, “Importantly, these activities are designed to be fun and to empower parents in being attuned to their baby’s development.” The app aims to communicate research findings on the cognitive neuroscience of development to the most important people in the baby’s life!

Maximising the adolescent brain: FutureEd18

What makes teenagers tick? Why does their behaviour seem to be erratic at times? How can we help them maximise their potential? What does the research on the adolescent brain tell us? These questions will be considered at the Learnus FutureEd18 conference, Wednesday February 7th, 2018. Speakers include Prof. Sarah-Jayne Blakemore (The Secret Life of the Teenage Brain) and Prof. Sophie Scott (fresh from her Royal Institution lectures). Further details.

New paper: Using Insight From Research to Improve Education

Annie Brookman-Byrne, a PhD student in the Centre for Educational Neuroscience, and Lia Commissar from the Wellcome Trust, have jointly published an article in the journal Mind Brain and Education. The paper summarises the International Mind, Brain, and Education Society pre-conference which was held in Toronto in 2016. The pre-conference was designed to share new research findings and host discussions about how best to move the field of educational neuroscience forward. The article captures discussions from the day and describes new Wellcome Trust funded work in response to the challenges. The article is freely available via this link.

Here are the key questions the paper considers:

- What have we learned from doing educational neuroscience research in the classroom?

- How can we close the gap between educational neuroscience research and classroom practice?

- Where do we want educational neuroscience to be in two years, and what do we need to make that happen?

Genetics and education – What’s the message?

Last week, The Times (@nicolawoolcock) reported a complaint by journalist Toby Young (@toadmeister) that he had been censored for writing that intelligence was largely genetic. What point was Toby Young trying to make by referring to genetic evidence and why was it censored?

According to the Times, Young’s blog argued that IQ is a strong predictor of how children perform in school exams; that schools are largely unsuccessful in raising the IQs of pupils; and that ‘intelligence is a highly heritable characteristic, which is to say that more than half of the variance in IQ at a population level is due to genetic differences’. The context of Young’s article was how he had moderated his early view about the transformative impact that good schools can have, based in part on learning about the greater contribution of genetics to variation in IQ.

There was a negative response to the blog on social media, including that it ‘had deeply nasty connotations’. Teach First (@TeachFirst ), a teacher training organisation, took down the blog, saying the article ‘was against what we believe in’.

Why is genetic data controversial in education?

Genetics is controversial in education because is it sometimes used to support arguments of determinism. In the deterministic narrative, schools have limited influence on children’s academic achievement in the face of more powerful forces, be it genetic variation or socio-economic status. Genetics additionally has negative historical associations with discrimination on the basis of race.

Was the scientific data interpreted correctly?

A recent meta-analysis of 42 datasets involving over 600,000 participants found consistent evidence for beneficial effects of education on cognitive abilities. The effect of schooling was a gain of approximately 1 to 5 IQ points for each additional year of education. Schooling therefore does have a small but measurable effect on intelligence. It is likely smaller than the effect of genetics and of socioeconomic status on IQ.

Importantly, however, genetic effects are not deterministic. If the environment is changed, the genetic effect may disappear. For example, despite the high ‘heritability’ of intelligence often reported in scientific studies, this genetic effect is reduced or eliminated under conditions of socioeconomic privation. When a poor educational environment holds children back, genetics effects can reduce: a study examining reading found reduced genetic effects on reading skills when teaching was poor.

Most of the evidence on genetic effects (‘intelligence is 50% inherited’ and so forth) concerns the differences between people. It does not focus on the absolute level that everyone is performing at (that is, the way people are similar). It is possible for the environment to improve everyone’s intelligence, even while the differences between them are for mainly genetic reasons. Therefore, genetic studies reporting heritability only give part of the picture.

This is relevant because national educational policy is often about changing the conditions for the whole population, (hopefully) raising the education level for all. To take a hypothetical example, the government might decree that schools spend double the amount of time teaching maths. The result would be that all children in the country would get better at maths (though perhaps worse at the topics they have less time for). Those at the top of the maths class might still be near the top, those at the bottom near bottom, perhaps for genetic reasons. The heritability of maths skills could stay the same, even though everyone had improved.

Studies focusing on genetic contributions to education are therefore mainly important for the question of gaps between children, and policy ambitions to narrow gaps. The debate considers the genetic and environmental causes of gaps. These gaps might not primarily stem from variation in school quality, which is the focus of Young’s blog. Indeed, when schools are very good, and in a society with low inequality, any remaining gaps would come from genetic differences (or ‘talent’). If we were to achieve the goal of perfect schools and equal societies, this would eliminate at least half the gaps in educational achievement between children. In that sense, data showing increasing heritability of educational achievement would be an index of progress on those goals (see Asbury and Plomin’s recent book ‘G is for Genes’ for more on this).

However, we should remember that education isn’t about populations, it is about individual children. None of the findings on genetics contradicts the fact that any individual can get better at any skill by working harder at it, irrespective of their genetic make up.

How can genetics benefit education?

Right now, the main message from genetics is that not all differences between children in educational outcomes are environmental.

In the future, based on progress in ‘precision’ medicine, the ultimate promise held out by the application of genetics to education is that we will be able to identify the optimal environments to maximise the genetic potential of each child – to realise their talent. This is a long way off. It requires identifying the biological basis of learning, no mean feat. And there are broader ethical issues to consider about genotyping one’s child and handing over the data to their school. But the promise shows the direction of travel: far from arguing for determinism, genetics is about identifying the best environment for individuals to thrive in.

Before then, as a society, we need to make progress on deciding how we feel about differences between children (in contrast to how well all children are performing). It may be that maximising every child’s (genetic) potential does not narrow the gaps between them. When education empowers every child to reach for the stars, we may have to accept that it is different stars the children are aiming at.

For more information

Here is a recent article giving an overview of the use of genetics in education. Here is a video that gives an introduction to the field: Professor Michael Thomas “Genetics and Education” from Learnus – Understanding Learning on Vimeo.