As children grow older, they tend to favour one hand over the other for certain tasks, particularly for writing or drawing. A child’s “handedness” is generally categorised as right, left or mixed, and tends to settle around the same time they acquire language – about four-years-old. It remains a persistent characteristic throughout our life. We now know that a child’s handedness says something about the organisation and function of their brain. See here for latest ideas on the development and evolution of handedness from Dr. Gillian Forrester (University of Westminster). Here are some of our recent papers in collaboration with Dr. Forrester:

Author Archives: admin

Save the Children advocates nurseries to be led by early years teachers – based on cognitive and brain science

The charity Save the Children has recently published a report entitled ‘Lighting up young brains‘. The report summarises some of the evidence on young children’s brain and cognitive development. The evidence is used to argue that in the first few years of life, children’s brains are particularly sensitive and that ‘as a child grows older it becomes much more difficult to influence the way their brain processes information’. The report advocates the government ‘to ensure that there is an early years teacher in every nursery in England by 2020’.

It is worth noting that, though there is relatively good understanding of the early phases of brain and cognitive development, the elevation of the early years as the most important phase predicting long-term cognitive and educational outcomes is more controversial (see here for discussion of the myth of the first three years). On the whole, early severe deprivation definitely has negative effects on children’s cognitive and brain development, and this is a clear target for policy. However, enrichment does not necessarily have equivalent positive effects. And a focus on the early years sometimes underplays the development that happens right through childhood and adolescence, when many of the more advanced cognitive abilities are emerging, and consequently underplays the need for education to support the emergence of such skills. Lastly, there is also a debate about the extent to which the brain loses its ‘sensitivity’, i.e., its ability to develop new skills, beyond the early years. Indeed, much of the evidence suggests lifelong plasticity for the acquisition of advanced cognitive skills, and loss of sensitivity only to acquire fine discriminations in low-level sensory and motor skills. Nevertheless, increasing training and expertise in early years teachers is a laudable aim.

Summary of ESRC Seminar on Cognitive Training in Children, MRC-CBU 11-12 Jan 2016

Blog written by Annie Brookman and Su Morris, originally published here.

On the 11th of January, the Medical Research Council (MRC) – Cognitive and Brain sciencesUnit (CBU) welcomed researchers and practitioners to Cambridge for a two-day seminar on cognitive training in children. The workshop opened with a presentation from Edmund Sonuga-Barke from the University of Southampton, examining randomised control trials of Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and assessing the importance of designing effective trials. Targeting the key cognitive deficits associated with ADHD (planning, inhibitory control, flexibility, and working memory) with multiprocess interventions has been shown to have a greater impact than targeting working memory by itself. However, the results of cognitive training interventions have not led to substantial associated improvement in ADHD symptoms. Sonuga-Barke argued that to maximise the effectiveness of interventions, they should be tailored to cognitive subgroups reflecting the heterogeneous nature of ADHD, and may be most effective when run alongside behavioural interventions. Rather than considering executive dysfunction as a causal factor of ADHD, it may be a comorbid factor, whereby functional impairment results when individuals exhibit both executive function deficits and ADHD symptoms.

Next up was Michelle Ellefson of the University of Cambridge, who spoke about the potential for using chess as a cognitive intervention in older children. Ellefson argued that chess can be seen as a non-computerised executive function training programme, as it requires flexible thinking, working memory, inhibitory control, and planning. It is also adaptive as players improve over time and continue to challenge each other. With this in mind, Ellefson used chess as a cognitive intervention in an after school activity for children in high poverty communities. Some improvement in executive function was seen, and the greatest improvement seemed to be in those who started with lower general cognitive ability. Analysis of the huge dataset is ongoing, and a next iteration is in the planning, with more precise measurements of intervention factors, such as time spent playing chess.

The third speaker was Emma Blakey from the University of Cardiff, who spoke about an executive function training programme for pre-schoolers. The programme saw an improvement in working memory skills following a short four-session training intervention. Blakey highlighted the importance of using a test task that is different from the training task to assess transfer. In this case, the training effect did transfer to a task sharing few features with the training task. Further, Blakey found far transfer to a mathematical reasoning task at three month follow up.

The final speaker for the first day was Usha Goswami of the University of Cambridge. Goswami spoke about her Wellcome Trust and EEF funded project investigating the effectiveness of a computerised programme called Graphogame Rime. Graphogame was developed in Finland, and is now played by all Finnish children when they are learning to read. While a phonetic version of the programme has been hugely successful in Finland, a rime version has been created for English speaking pupils, since English has many more irregularities than Finnish. Graphogame Rime helps children to use rimes in word-learning, such as ‘at’ in ‘cat’. This enables children to read groups of words with similar rimes, such as mat, sat, chat. Goswami hopes to find that this will be more effective than phonological training, and the project is ongoing. We look forward to hearing the results.

Day two of the seminar was kicked off by Sam Wass from the University of East London, who talked about his research on training attentional control in infants. With only a short training period, a significant improvement in attention was measured, however after 6 months only ‘sequence learning’ improvements remained. This suggests that infants, compared to older children, require a shorter length of cognitive training for improvements to be measured, however the effects may dissipate more rapidly, possibly due to increased plasticity in this age group.

Torkel Klingberg from the Karolinska Institute in Sweden presented data from a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) intervention study which predicted responses to mathematical and cognitive training in children. Four intervention groups were compared – reading, reading and working memory, reading and numberline training, and numberline training with working memory – with outcome measures differing from the training. The maths improvement was greatest in the numberline and working memory training group. Participants with low working memory scores at baseline showed the poorest improvement in working memory after training, suggesting that factors driving poor working memory development continue to limit progress even during working memory training interventions. It is suggested that these factors are genetic (DAT-1 and DRD2) and neural (striatum). Brain activations predicted the type of training which participants would best respond to, therefore fMRI diagnosis could be an effective alternative to examination by neuropsychologists.

Duncan Astle from the MRC-CBU discussed his resting state magnetoencephalography (MEG) study which focussed on functional connectivity within the brain. If different areas of the brain concurrent oscillatory activity, it is likely that these areas are working together. A cognitive training group was compared with an active control group, and post-test resting state network connectivity was shown to improve in the test group, correlating with behavioural measures of working memory improvement. It was suggested that the cognitive training had an impact on phase amplitude coupling which results in improving connectivity rather than isolated changes in specific brain areas.

The final speaker was Susan Gathercole from the MRC-CBU, who was also one of the conference organisers. Gathercole spoke about the current state of working memory training studies and how we might best move forward. The gold standard of training studies are those that are randomised control trials which include an active control group rather than a waiting control group. Many of these studies have shown no or minimal far transfer. Gathercole argued that rather than aiming for far transfer, we first needed to understand near transfer. By understanding the mechanisms involved, we will be able to suggest why far transfer effects are inconsistently observed in current studies.

One of the key areas of discussion that arose throughout the seminar was how best to design interventions. Minimal training is ideal because of the time and money commitment, but we don’t yet know how much is needed to achieve the biggest effects. Some research suggests that effects tend to plateau following 15 to 20 training sessions. A recent move in the training literature is towards embedding cognitive training within the subject domain. Although this sounds like it may lead to greater transfer (within that domain) we are not yet sure if this is the case. Alan Baddeley referred to stroke patients who are trained to climb stairs in the clinic, yet need to be trained again to climb stairs in a different setting. Even though the same skill is required, it needs to be trained within each setting. It remains to be seen how well transfer will work for cognitive training within specific subject domain. The final discussion of the seminar focussed on the need to measure real-world abilities, rather than relying on lab measures. We need to make sure our research is applicable to the classroom and home, and this may require video-recording individuals in their natural setting, and coding their behaviour.

The workshop brought together exciting research on cognitive training in a variety of different fields, and facilitated valuable discussions about how to proceed with future research. The sessions demonstrated the importance of examining research methods and cognitive theory, as well as sharing findings and conclusions. The workshop offered a great opportunity to listen, to question and to network, and was certainly a very enjoyable and interesting event.

Current Issues in Educational Neuroscience: A workshop sponsored by the Bloomsbury and UCL Doctoral Training Centres

Adolescents and multi-tasking

Blog written by Dr. Iroise Dumontheil and originally published here

Humans are social beings. We have evolved to function in groups of various size. Some researchers argue that the complexity of social relationships which require, for example, remembering who tends to be aggressive, who has been nice to us in the past, or who always shares her food, may have been an evolutionary pressure leading to the selection of humans with bigger brains, and in particular a bigger frontal cortex (see research by Robin Dunbar).

However, we do not always take into account the perspective or knowledge of a person we are interacting with. Boaz Keysar and laterIan Apperly developed an experimental psychology paradigm which allows us to investigate people’s tendency to take into account the perspective of another person (referred to as the “director”) when they are following his instructions to move objects on a set of shelves. Some of the slots on the shelves have a back panel, which prevent the director, who is standing on the other side of the shelves, from seeing, and knowing, which objects are located in the slots. While all participants can correctly say, when queried, which object the director can or cannot see, adult participants, approximately 40% of the time, do not take into account the view of the director when following his instructions.

In a previous study, Sarah-Jayne Blakemore (UCL), Ian Apperly (University of Birmingham) and I, demonstrated that adolescents made more errors than adults on the task, showing a greater bias towards their own perspective. In contrast, adolescents performed to the same level a task matched in terms of general demands but which required following a rule to move only certain objects, and did not have a social context.

The Royal Society Open Science journal is publishing today a further study on this topic, led by Kathryn Mills (now at the NIMH in Bethesda) while she was doing her PhD with Sarah-Jayne Blakemore at UCL. Here, we were interested in whether loading participants’ working memory, a mental workspace which enables us to maintain and manipulate information over a few seconds, would affect their ability to take another person’s perspective into account. In addition, we wanted to investigate whether adolescents and adults may differ on this task.

What would this correspond to in real life? Anna is seating in class trying to remember what the teacher said about tonight’s homework. At the same time her friend Sophie is talking to her about a common friend, Dana, who has a secret only Anna knows. In this situation, akin to multitasking, Anna may forget the homework instruction or spill out Dana’s secret, because her working memory system has been overloaded.

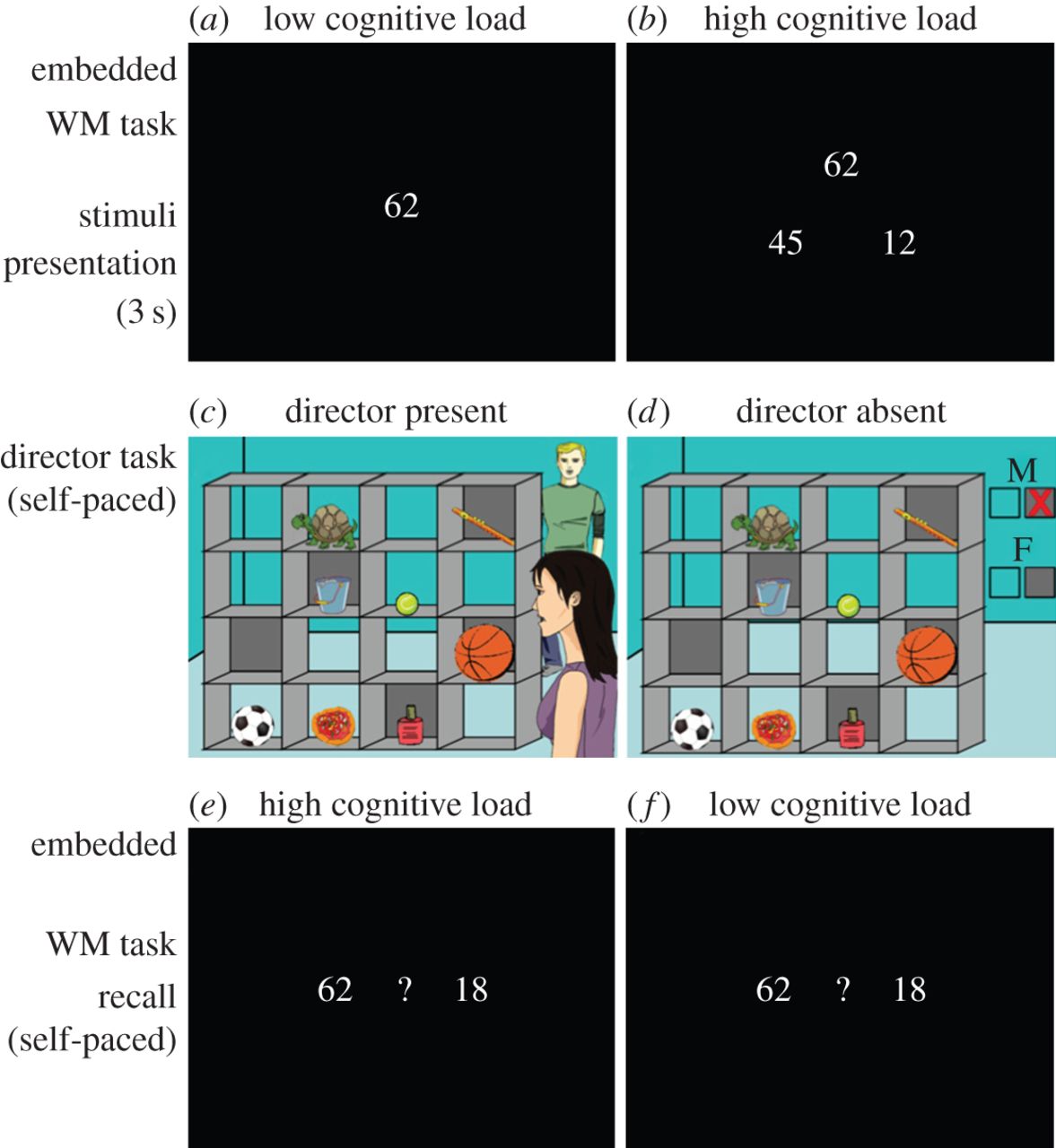

Thirty-three female adolescents (11-17 years old) and 28 female adults (22-30 years old) took part in a variant of the Director task. Between each instruction given by the director, either one or three double-digits numbers were presented to the participants and they were asked to remember them.

Overall, adolescents were less accurate than adults on the number task and the Director task (combined, in a single “multitasking” measure) when they had to remember three numbers compared to one number. In addition, all participants were found to be slower to respond when the perspective of the director differed from their own and when their working memory was loaded with three numbers compared to one number, suggesting that multitasking may impact our social interactions.

Presentation of multitasking paradigm (image published in Royal Society Open Science paper). For each trial, participants were first presented with either (a) one two-digit number (low load) or (b) three two-digit numbers (high load) for 3 s. Then participants were presented with the Director Task stimuli, which included a social (c) and non-social control condition (d). In this example, participants hear the instruction: ‘Move the large ball up’ in either a male or a female voice. If the voice is female, the correct object to move is the basketball, because in the DP condition the female director is standing in front of the shelves and can see all the objects, and in the DA condition, the absence of a red X on the grey box below the ‘F’ indicate that all objects can be moved by the participant. If the voice is male, the correct object to move is the football, because in the DP condition the male director is standing behind the shelves and therefore cannot see the larger basketball in the covered slot, and in the DA condition the red X over the grey box below the ‘M’ indicates that no objects in front of a grey background can be moved. After selecting an object in the Director Task, participants were presented with a display of two numbers, one of which corresponding to the only number (e) or one of the three numbers (f), shown to them at the beginning of the trial. Participants were instructed to click on the number they remembered being shown at the beginning of the trial.

Find out more

- News article: Adolescents are less adept at multitasking than adults, psychological study suggests

- Read the study: “Multitasking during social interaction in adolescence and early adulthood”

- Dr Iroise Dumontheil

- Department of Psychological Sciences, Birkbeck, University of London

- Royal Society Open Science

CEN seminar, 4pm 10th March: Dr Charles Chew, Ministry of Education, Singapore

Please join us at 4pm, 10th March, SSRU seminar room, 18 Woburn Square. Dr. Charles Chew, Ministry of Education, Singapore will be talking about: Development of Innovative Bio-physics Demonstrations for Constructivist Teaching using the Predict-Observe-Explain [POE] Instructional Approach.

Neuro-hit or neuro-myth?

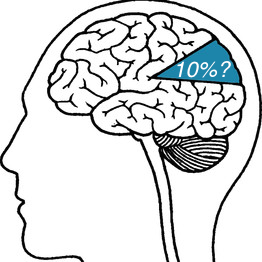

CEN has just launched a new web resource on neuromyths!

Neuromyths are common misconceptions about brain mechanisms, which are taken for granted in today’s society. Some of these myths have taken root amongst educators and have influenced educational techniques. Some myths are wonderfully bizarre (we only use 10% of our brains!). Some myths have seeds of truth but have led to educational techniques without scientific grounding (e.g., the myth that left-brain=logic right-brain=emotion and creativity has a seed of truth in research on functional brain lateralisation). Other myths appeal to strong intuitions but the science is only assumed (girls and boys have different cognitive abilities).

Entitled ‘Neuro-hit or neuro-myth?‘, we give up-to-date evaluations of a range of neuromyths, including links to recent scientific resources and articles.

This resource was supported by a Wellcome Trust Institutional Strategic Support Fund Award.

Two new ESRC CASE PhD studentships now inviting applications

Would you like to complete your PhD on an exciting project linked to educational neuroscience, which combines experience in both academic and commercial sectors?

The effect of ambient noise on on early learning in a classroom environment

Under the supervision of Dr. Natasha Kirkham and Professor Denis Mareschal, this studentship will be focussed on understanding the impact of ambient or environmental noise on early learning in a classroom environment, and will be run in collaboration with our partner on the project, Cauldron (http://cauldron.sc), a resource-developer for online experiments This project will require coding/programming experience and we encourage students with both developmental and cognitive science backgrounds to apply.

Closing date for applications is 1st March 2016. Informal inquiries can be made to Natasha Kirkham: n.kirkham@bbk.ac.uk

The effect of technology use on the development of adolescent executive function skills

Closing date for applications is 26th Feb 2016. Informal inquiries can be made to Iroise Dumontheil: i.dumontheil@bbk.ac.uk. Further details here.

Would you like to do a PhD in Educational Neuroscience?

Bloomsbury Doctoral Training Centre Studentship Applications are now invited.

Applications are now open for ESRC studentships via the Bloomsbury Doctoral Training Centre, which offers a training route in Educational Neuroscience. Further details on the application process are available on the DTC website here.

The closing date for applications is Friday 5 February 2016.

CEN Research Group spring meeting schedule

The CEN Research Group, which is open to those interested in the latest developments in educational neuroscience, meets weekly at 4pm on Thursday afternoons.

Our spring schedule is now available here. Upcoming topics include the use of philosophy to develop reasoning skills in primary schools, spatial ability and science performance, chess in schools, and an investigation of cognitive deficits in children with cerebral palsy and how these impact mathematical ability.

The CEN Research Group is open to faculty members, postdoctoral fellows, and students at Birkbeck and UCL (especially those on the Educational Neuroscience and Developmental Sciences masters, and PhD students studying relevant topics). It is also open to educationalists, educational psychologists, and interested teachers. Meetings aim to enable an atmosphere of informal discussion of the latest findings in and challenges for neuroscience and psychology relevant to education. If you would like to attend, please contact us at: centre4educationalneuroscience@gmail.com