The CEN received an enquiry from a parent whose 17-year-old daughter has autism and is preparing to move to university. The daughter is bright but has executive functioning difficulties in ‘not being productive’ and being ‘slow at everything’. Executive functioning is the technical term for processes of cognitive control, including attention, task selection, and planning. It also includes working memory: keeping information in mind and manipulating it to achieve current task goals. The parent enquired whether current research points towards any specific structured programmes designed to develop executive functioning skills that would benefit their daughter.

We asked Dr. Petri Partanen, one of the leading researchers in planning skills in children with learning difficulties, based at the Mid Sweden University, who offered the following advice.

“I will try my best to answer the question, considering interventions that can be managed at home and that might bring improvements in executive functions. This is general advice that might not be suitable in the specific case, since that would require more background information – particularly since there are many different cognitive profiles underlying the diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorder (ASD). As I have been working as a practitioner with children and youth with learning difficulties, I will also share some thoughts from that perspective.

To start with I would say that there is scarce evidence of specific methods for improving executive functions, including planning via training protocols implemented outside the school context, for children and youth with ASD.

I am hesitant to recommend working memory training, even though there are some studies with children and adolescents with ASD showing positive effects (see for example, this study by Weckstein et al., in 2017). The dilemma here is that such training regimes build on the idea of training abilities separated from the content and context. Thus, they require the child to process far transfer. Far transfer means when learned knowledge and skills are extended from the taught context to another dissimilar context. Far transfer still needs to be proven, in my humble opinion.

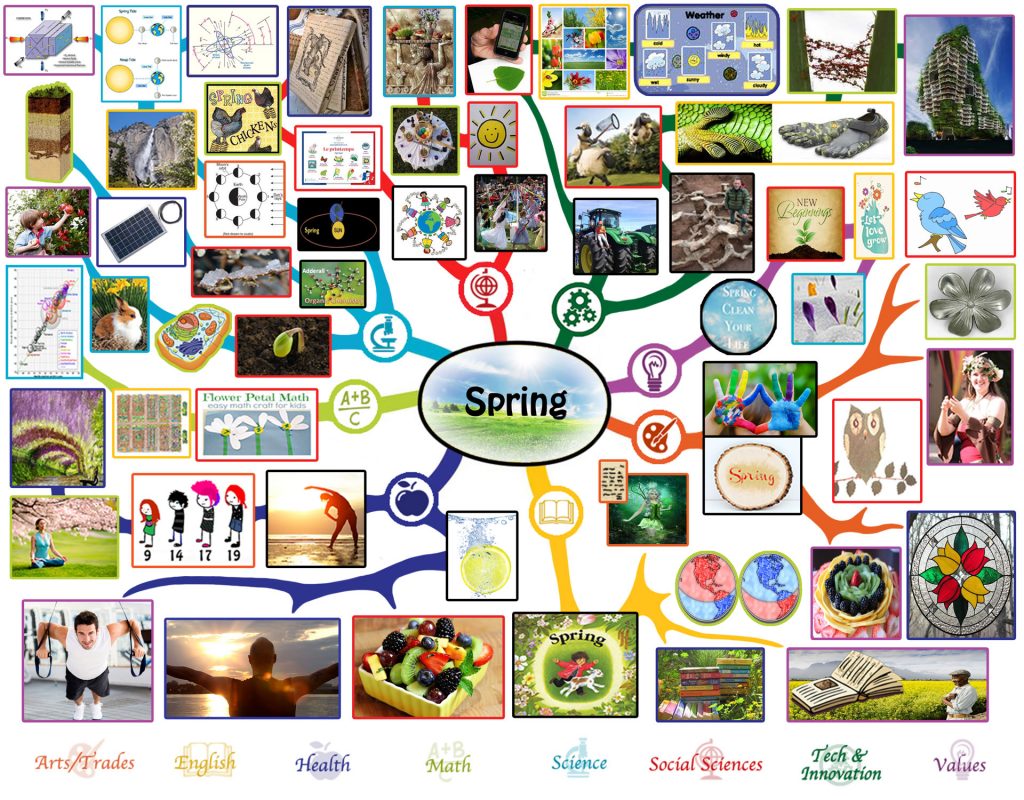

There are some pilot studies which indicate that combining such cognitive stimulus training programs with metacognitive strategy coaching might increase the effects of such interventions on executive functions (see for example this study by Macoun and colleagues published in 2020). Metacognitive training teaches children explicit strategies about how to apply their current knowledge to new situations. For example, in the aforementioned pilot study, 6-12 year old children with ASD were taught metacognitive strategies using a 5-step script: (1) identify the issue/difficulty, (2) state the reason for the issue/difficulty, (3) select and implement a strategy, (4) evaluate the outcome of the strategy, and (5) once a strategy works, celebrate success (i.e., provide positive reinforcement).

On the other hand, the CogMed working memory training program can be managed at home quite easily, and in combination with a raised metacognitive awareness it can stimulate the adolescent to apply cognitive functioning in different situations – for example through a discussion about important strategies that can be used in studying. Sometimes this discussion can be dealt with by parents, sometimes it has to be someone else, a counsellor or educational psychologist following this. I do think there is ASD support organised at universities in UK, which will be very important. In Sweden there are centers at each university, and I have followed several cases of adolescents with ASD that have been successful, so there are grounds for optimism.

I am particularly interested in interventions that help adolescents become metacognitively aware and help them to find good academic self-regulation strategies, and hopefully together with raised awareness among teachers, implement the study strategies.

As an experienced practitioner, I would say that this would be one of the important keys to success, and help the soon-to-be-adult to plan their studies, try out strategies that fit them, and develop some planning skills. I think finding opportunities as a parent to discuss these questions with the adolescent will be important. This could be very helpful for an adolescent taking the step to university studies, and clearly the adolescent besides challenges has a lot of cognitive resources and strengths.

If we instead look at intervention protocols addressing more specific subject skills for children and adolescents with ASD, there is much more promising research. Particularly, Self-Regulated Strategy Development (SRSD) is well-researched and includes planning facilitation in different subject areas like reading, writing, and mathematics (see, for example this systematic review of writing instruction by Asaro-Saddler published in 2016, and this meta-analysis on reading interventions by Sanders and colleagues in 2019). However, the SRSD protocol is meant to be implemented by teachers and not parents. These protocols still might inspire what to focus on in the support, even in the role as a parent.”

Wednesday 24th November at 4 pm (UK time)

Wednesday 24th November at 4 pm (UK time)