We were contacted by a local authority in England that asked about the overlap between Special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) and deprivation, and what a school could do to help these students.

It is important to be clear from the outset: SEND should not be treated as simply another label for deprivation. SEND arise for many interconnected reasons, including genetic, neurodevelopmental, and biological factors.

At the same time, there are well-documented associations between SEND and socioeconomic disadvantage (e.g. around 43.8% of pupils with an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP) were eligible for Free School Meals), and ignoring these links would also be misleading. What matters is understanding that the relationship between SEND and deprivation is not uniform. It looks different depending on the type of need, the severity of difficulties, and the broader context in which children and families live.

Why SEND and deprivation often overlap — but not always

On average, children and young people with SEND are at risk for lower educational outcomes (Tuckett et al., 2021), which can feed into lower socioeconomic outcomes in adulthood. This partly accounts for why areas with higher deprivation often show higher recorded rates of SEND. In addition, many neurodevelopmental differences are heritable, making it more likely the parents of children with SEND also have difficulties. Where parents themselves have undiagnosed or unsupported SEND, families may face unstable employment, poorer health, difficulty navigating services, and greater exposure to stress and adversity. These pressures can affect school attendance, engagement with education, and the consistency of support children receive.

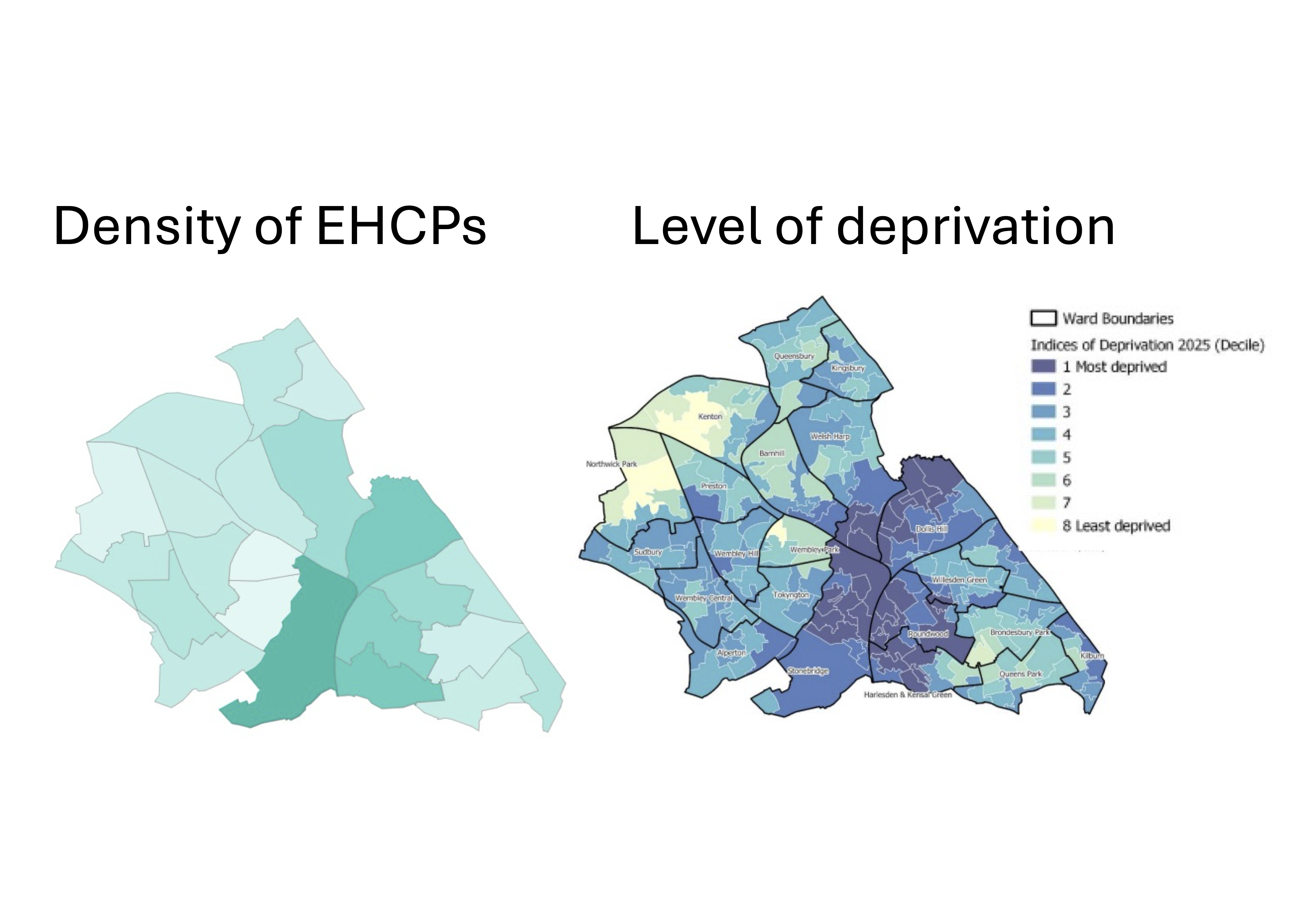

However, this pattern varies by type of SEND. For some needs, particularly more severe or biologically rooted conditions, the link with deprivation is weaker. For others, such as social, emotional and mental health difficulties, the association with socioeconomic disadvantage may be stronger. In these cases, relatively mild underlying neurodiversity can be exacerbated by environmental stressors, leading to greater difficulties being observed in school. As a result, neighbourhood-level “maps” of SEND prevalence can look very different depending on which needs are examined.

This is why it is unhelpful to talk about “SEND and deprivation” as though they were a single phenomenon.

Attendance, belonging, and relationships matter for everyone

One area where SEND and deprivation clearly intersect is attendance. Importantly, attendance is not just an administrative or academic metric. Regular attendance supports confidence, social participation, and a sense of belonging. Evidence increasingly shows that non-attendance among pupils with SEND is often linked to schools not fully meeting their needs, and that feeling connected and valued in school strongly predicts whether children attend (Cameron et al., 2025).

Crucially, this applies across the board. Whether difficulties are driven more by neurodevelopmental factors or by socioeconomic pressures, positive relationships with education professionals and a strong sense of belonging help children engage with learning.

Early years matter more than labels

For many children with SEND, especially those with intellectual or developmental delays, progress is shaped less by labels and more by the timing, quality, and consistency of early support. Some children benefit from entering education at a developmental stage that better matches their learning needs, rather than strictly by chronological age. However, flexibility in school entry only works if it is paired with guaranteed access to high-quality early provision.

Evidence suggests that when children miss formal early years education altogether, outcomes are worse—particularly for children from low-income or language-minority backgrounds Campbell (2023). What matters most is access to high-quality, inclusive early years settings, not simply delaying or accelerating formal schooling.

What the evidence tells us about early support

Research from the UK and internationally points to a consistent message: quality and access to support matters more than policy labels. Early years programmes that combine educational input with family support show benefits for children later identified with SEND, particularly for less complex needs (Carneiro et al., 2025, IFS). Earlier access to structured, high-quality provision is associated with better literacy and numeracy outcomes in the early school years (Vandecruys et al., 2026).

Parental involvement is a particularly powerful lever. Reviews of intervention studies show that the strongest effects come from multi-component approaches that combine structured parent–child activities with close collaboration between families and schools. Supporting families in a systematic, joined-up way improves both wellbeing and learning, especially in lower socioeconomic contexts (Hamid et al, submitted).

Inclusive systems need layered solutions

Because both SEND and deprivation are complex and inter-related, solutions must be multi-faceted. Educational responses alone are not enough. Effective systems:

- front-load support in the early years

- prioritise belonging and attendance

- embed evidence-based classroom practices that benefit all learners

- and include safeguards so that disadvantaged families are not excluded from flexibility or choice

Many classroom practices validated for SEND—such as explicit teaching, high-quality feedback, scaffolding, and structured support—also benefit the wider cohort. Scaling these practices as part of everyday teaching helps avoid over-reliance on individual diagnoses while still responding to genuine differences in need.

At the same time, broader societal factors—poverty, health, housing, and access to services—shape what schools can realistically achieve on their own. Inclusive education is necessary, but not sufficient, to address inequality.

In summary

SEND is not simply a proxy for deprivation, but neither is it separate from it. The relationship between SEND and SES varies by type of need and by context. What cuts across both is the importance of early, high-quality provision; strong relationships; a sense of belonging; and coordinated support for families. Systems that recognise this complexity—and design for it—are far more likely to improve outcomes for children with SEND and reduce long-term inequalities.

References:

Campbell, T. (2023). Whose entry to primary school is deferred or delayed? Evidence from the English National Pupil Database. Review of Education, 11, e3409. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3409

Cameron, C., Villadsen, A., Roberts, A., Evans, J., Hill, V., Hurry, J., Johansen, T., Van Herwegen, J., & Wyse, D. (2025) School absence and (primary) school connectedness: evidence from the Millennium Cohort Study. London Review of Education , 23 (1) , Article 5. 10.14324/LRE.23.1.05.

Carneiro, P., Cattan, S., Conti, G., Crawford, C., Farquharson, C., & Ridpath, N. (2025). The short-and medium-term effects of Sure Start on children’s outcomes. The Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Vandecruys, F., Vandermosten, M., & De Smedt, B. (2026). Education as a natural experiment: The effect of schooling on early mathematical and reading abilities and their precursors. Journal of Educational Psychology, 118(1), 70–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000958