Creativity is not very well understood from a neuroscientific perspective. One theory growing in prominence is that creativity involves the coupling of brain networks which normally work in opposition, allowing the brain to engage both in free associative processes (making unusual connections) and more focused executive processes (evaluating and assessing possible ideas). What is reasonably undisputed is society’s need for creativity – and for individuals who can come up with creative solutions – but how can teachers best help children develop these creative skills?

Creativity is not very well understood from a neuroscientific perspective. One theory growing in prominence is that creativity involves the coupling of brain networks which normally work in opposition, allowing the brain to engage both in free associative processes (making unusual connections) and more focused executive processes (evaluating and assessing possible ideas). What is reasonably undisputed is society’s need for creativity – and for individuals who can come up with creative solutions – but how can teachers best help children develop these creative skills?

Eniko Bereczki is a researcher in pedagogy and psychology with a particular interest in creativity. She has been looking at teachers’ creativity beliefs and the implications for classroom practice. Here she talks about her findings with the CEN.

Eniko Bereczki is a researcher in pedagogy and psychology with a particular interest in creativity. She has been looking at teachers’ creativity beliefs and the implications for classroom practice. Here she talks about her findings with the CEN.

Author: Enikő Orsolya Bereczki, Faculty of Pedagogy and Psychology, Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE) in Hungary

What does recent research tell us about teachers’ creativity beliefs and what are the implications for classroom practice?

How well creativity is implemented in education is highly dependent on teachers’ beliefs about it. These beliefs have been extensively investigated over the past 25 years; early studies found that although teachers appreciated creativity, their beliefs were often misaligned with the scientific evidence. Common misconceptions included the idea that creativity is solely concerned with originality, that it is an inborn talent that cannot be nurtured and that it mainly relates to arts and humanities. The research suggested that these misconceptions were likely to act as barriers to fostering creativity in the classroom.

In our systematic literature review[i] of in-service K-12 teachers’ beliefs about creativity we wanted to know if teachers’ beliefs about creativity had become more aligned with the scientific literature in recent years and to find out more about how teachers’ views translate into classroom practice.

There has been a growing recognition of creativity across the curriculum in recent years among classroom teachers.

We found 53 studies published between 2010 and 2015 examining teachers’ beliefs about creativity. Research was carried out all over the world including four studies from the UK. One of our major findings was that teachers’ beliefs heavily depend on the context of investigation: even teachers coming from the same geographical areas, the same cultural background or teaching the same subjects and age groups may hold very different views. Nevertheless, we identified several recurrent themes in teachers’ beliefs on the nature of creativity:

- Teachers generally support the idea that creativity can be nurtured. The idea that creativity is an inborn talent is still held in certain contexts, especially those in which teachers lack specific creativity training.

- Teachers generally agree that creativity can manifest in any domain; in Western cultures, there is a slight bias towards art-related subjects while in the East the bias is towards science.

- Teachers rarely recognise that both originality and appropriateness are joint requirements for creativity, with many educators placing emphasis solely on originality. This risks undervaluing some of the skills and knowledge which contribute to the creative process, and may create an environment in which creativity competes with academic learning instead of supporting it.

- The idea that creativity requires both originality and appropriateness is supported by highly-accomplished expert teachers, who might therefore play an important role in promoting research grounded beliefs about creativity.

- Teachers still sometimes have trouble recognizing creative students in the classroom and are often instead positively biased towards students with high intellectual abilities and good behaviour. This may leave creative potential unrealised in the classroom.

- Teachers generally have positive attitudes towards creativity, feel capable of fostering it and perceive themselves as doing so. Cross-validation of data, however, often highlights incongruence between beliefs and enacted classroom practices.

- Teachers are aware of several strategies that promote students’ creativity, though some aspects were overlooked and others overemphasized. Teaching divergent thinking and providing active learning opportunities were seen as creativity fostering strategies.

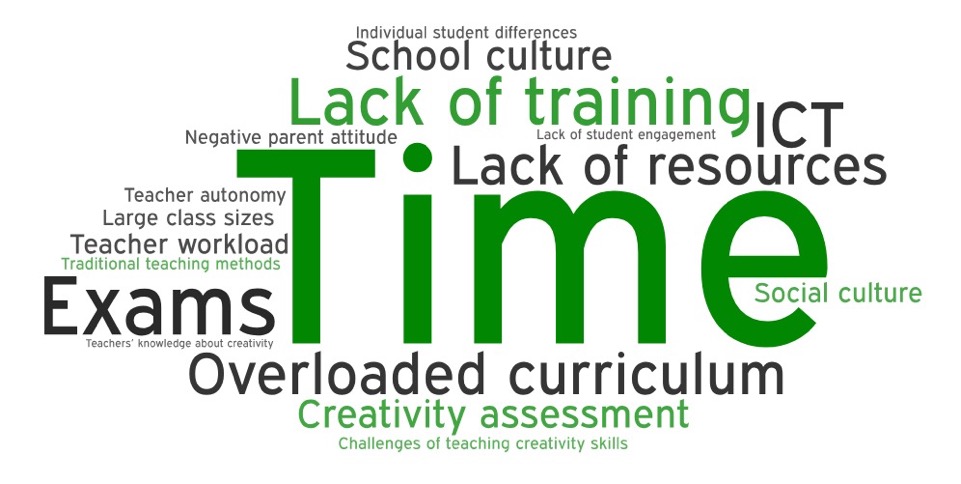

Teachers perceive several barriers, and few enablers, to fostering creativity in the classroom. Lack of time, overloaded curriculum, lack of training, standardized tests and difficulties in assessing creativity are the most widely cited barriers in recent literature. Teachers still need more help to translate their positive beliefs about creativity to creativity-fostering classroom practices

Teachers still need more help to translate their positive beliefs about creativity to creativity-fostering classroom practices

Of 53 studies on teachers’ beliefs about creativity, 19 investigated the link between teachers’ espoused beliefs and enacted classroom practice. The most important findings were:

- Teachers’ practices reflect beliefs which are in misalignment with research. For example, teachers who stressed the originality aspect of creativity tended to ask students to generate unique responses, while overlooking tasks requiring both originality and appropriateness.

- Teachers find it difficult to translate positive beliefs and those in line with research to creativity-fostering classroom practices. Studies which included classroom observation showed that there were teachers with positive beliefs and considerable knowledge about creativity who did not incorporate creativity-fostering tasks in their lessons.

- Teachers may perceive that they foster creativity in the classroom while their students or school leaders may have different perspectives.

Policy makers and teacher education can do a lot to help teachers develop research-aligned creativity beliefs and implement creativity-fostering practices.

Based on our study, we believe there are several options open to policy makers:

- Beyond establishing creativity as an important learning goal in the curriculum, provide research-based definitions and guidance on how to nurture it across the various subject areas.

- Invest in the development and acquisition of resources and materials that teachers can use to promote and assess creativity.

- Create opportunities for teachers to develop and share best practice on promoting and assessing creativity across the curriculum. Encourage schools to promote creativity-fostering cultures.

- In teacher education and development, provide training on creativity and its nurture. Training should emphasise how to conceptualize, recognize, explicitly teach for and assess creativity. It should also explicitly address teachers’ beliefs about creativity.

Teachers themselves can make a real difference

Finally, we would like to share some ways in which teachers can use current creativity research to inform their creativity beliefs and translate them into creative classroom practice:

- Reflect on your own beliefs about creativity in the light of research results.

- What We Know About Creativity? is a research brief published by Partnership for 21st century skills, which is a good starting point for examining beliefs and knowledge about creativity.

- Creativity in the classroom is a learning module published by the American Psychological Association which gives an overview of the use of creativity in a classroom through interviews with renowned scholars in the field.

Infuse creativity in the curriculum instead of treating it merely as an extra-curricular learning objective. These resources show that even with slight adjustment creativity can become part of daily teaching practice:

- Cultivating Creativity in Standards-Based Classrooms, Dr. Marilyn Price-Mitchell’s post on Edutopia on how in even highly-structured classroom environments teachers can foster creativity.

- Killing Ideas Softly, Dr. Ronald Beghetto’s talk on how making slight changes to existing practices can result in new ways of thinking and acting, which lead to more creativity in the classroom.

- Weaving Creativity Into Your Curriculum, a podcast episode featuring Dr. Cyndi Burnett’s talking about teaching for creativity across the curriculum.

- In education, what is assessed counts: develop strategies to assess and reward creativity in your classroom.

- In her post Assessing Creativity Susan M. Brookhart offers some practical tips on how to asses and reward student creativity in the classroom.

[i] Bereczki, E. O., & Kárpáti, A. (2018). Teachers’ beliefs about creativity and its nurture: a systematic review of recent research literature, Educational Research Review, 28, 25-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.10.003 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1747938X17300490